Upon reading our article on Fredric Jameson’s notion of postmodernism in connection with Celine Song’s Past Lives, it occurred to me that there may be two distinct ways one might practice hermeneutics on this contemporary text. The first, and perhaps most obvious, is that which Megan Feeney undertakes in her Cineaste review of Song’s film – namely, a laudatory appreciation of Song’s integration of her rich playwright background into the film’s cinematic language, alongside contextual trivia that enriches the viewing experience. This mode of critical analysis can indeed be illuminating for viewers eager to learn more about this first-time filmmaker. However, I would argue that a more compelling study of the film emerges when we approach Past Lives as a fundamentally postmodern work – an unapologetic nostalgia film that purposefully employs the device of pastiche to generate a crisis of historicity for the viewer, producing a disorienting experience of hyperpresence that mirrors the estranging sensorium of the immigrant condition.

The first indication of this intention – to reduce the viewer’s experience to the present moment – appears in the film’s title, specifically through the word “Past”. When paired with “Lives” and introduced alongside the Korean concept of inyun, Song gestures toward the Buddhist belief in reincarnation and fate. Past Lives, in this sense, is a relational term, one whose meaning can only be discerned through a point of reference. As we move forward and backward through the life of the protagonist, Nora, the viewer is left uncertain whether we are currently inhabiting a “past life”, or if the moment onscreen is instead inflected by some other, unseen past lives.

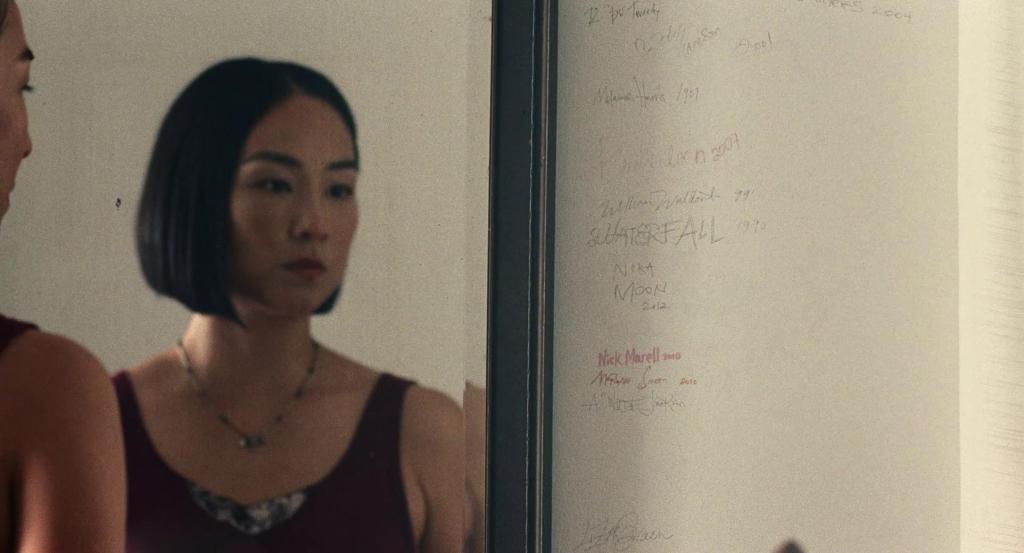

Another dimension of Past Lives that attests to Song’s postmodern sensibility lies in her multi-layered intertwining of autobiographical material through the mirroring of her own artistic works, Endlings and Past Lives. Endlings, Song’s real-life off-Broadway play, “features a Korean-Canadian playwright living in Manhattan and married to a white writer, and … grapples strenuously with thornier issues of diasporic identity and related representational politics” (Feeney) – a premise that directly carried into her cinematic rendering of Past Lives. Within the film, Nora – who physically resembles Celine Song – is seen attending theatre workshops in which an actress, resembling Nora, performs lines about her immigrant experiences. As these narratives fold into one another, Endlings and Past Lives begin to refract, as do the multiple physical iterations of Song’s likeness. The entanglement of temporal, historical, and diegetic markers – much like the film’s title – undermines the viewer’s ability to locate stable coordinates within Song’s autobiographical and fictional worlds. This, in turn, produces a disorienting state of hyperpresence through the mise-en-abyme’s spatialization of time.

A further element that, I argue, classifies Past Lives as a postmodern nostalgia film is its reversion to the affective mode of “yearning”. “Yearning” is a term popularized in the current internet age, describing a mode of Freudian repression central to cultural production during the late aughts and early 2010s in works such as Joe Wright’s Pride and Prejudice, Nicholas Sparks’s film adaptations, and other romance dramas of the period. TikTok trends and YouTube videos with the hashtag #bringyearningback reveal a nostalgic impulse in contemporary popular culture – a longing for the emotional intensity of romantic restraint. This demand has been met by studios through the resurgence of romance films and dramatic television series such as The Summer I Turned Pretty and Bridgerton, both of which capitalize on postmodern nostalgia via the pastiche of period dramas.

Song similarly mobilizes this affective framework by structuring Past Lives around Nora and Hae Sung’s coming of age, their cyclical reconnections every twelve years, and their eventual separation – all underscored by the Korean notion of inyun. These narrative rhythms cultivate suspense as audiences yearn for the two childhood sweethearts to reunite. Song’s decision to end the film with Nora’s choice to remain with Arthur intensifies the affect of repression: the fantasy of Nora’s union with Hae Sung becomes all the more potent precisely because it remains unfulfilled. A subtler but equally deliberate aspect of Song’s nostalgic aesthetic lies in her attention to the period pastiche of the 2010s – through hairstyles, clumsy Skype calls with wired headphones, and skinny jeans – all evoking a cultural moment that feels recent yet strangely depoliticized. Moreover, Song’s insistence on shooting the film on 35mm – a costly and increasingly rare format – invites viewers into a false historicity that parallels the effect of pastiche itself. Through these strategies, Past Lives unabashedly situates itself as a postmodern nostalgia film.

How, then, do these postmodern features of Past Lives intersect with the immigrant experience? I would argue that the postmodern condition is, in fact, the immigrant condition. Jameson describes postmodernism as a cultural logic of late capitalism, “characterized by globalization and the commodification of everything”. Immigration often arises from this same global system of movement in pursuit of capital – colloquially framed as the search for “more opportunities”. Yet the cost of this migration is the renunciation of a way of life, a home, and a network that collectively constitute one’s ‘past life’. Nostalgia thus becomes one of the most powerful affective experiences of migration, and the yearning for a past that can never be reclaimed forms an integral part of the immigrant psyche.

Song’s film is postmodern precisely in how it commodifies this affective experience of nostalgia – rendering nostalgia itself nostalgic. The film’s crisis of historicity, evidenced by its obscured temporal markers, mirrors the immigrant subject’s hyperpresence: an inability to access the past or imagine the future when uprooted from all familiar reference points. As Jameson observes, the postmodern work is less concerned with “somebody telling about their feelings or affects” and instead presents “somebody testifying to their flow of experience”. Past Lives, I argue, is a quintessential postmodern “surface work”. Its defining features – the waning of affect through calibrated intensities of nostalgia, the crisis of historicity via obfuscated temporal and diegetic markers, and the pervasive use of pastiche through 35mm film, costuming, set design, and the reincarnation of a once-beloved romance subgenre – together exemplify the postmodern sensibility, and as such the disorienting immigrant sensibility.

Leave a comment