[excerpt from in-class Midterm]

In Robert Clouse’s Enter the Dragon, Bruce Lee’s role as the enigmatic protagonist “Lee” closely mirrors his public persona. His success in the film industry stems from his unique upbringing as both a child actor in Hong Kong cinema and a performer on American television. The combination of these experiences allowed Lee to understand that American audiences preferred martial arts sequences that felt naturalistic—simulating realism and phenomenologically suggesting that such feats could be executed by viewers themselves. Moreover, Lee’s bridging of Hong Kong and American film industries enabled Warner Bros. and Golden Harvest to co-produce Enter the Dragon. This convergence of markets and identities exemplifies Andrew Higson’s concept of “transnational cinema,” which highlights the cross-border dynamics of production, distribution, and reception that have shaped cinema from its inception.

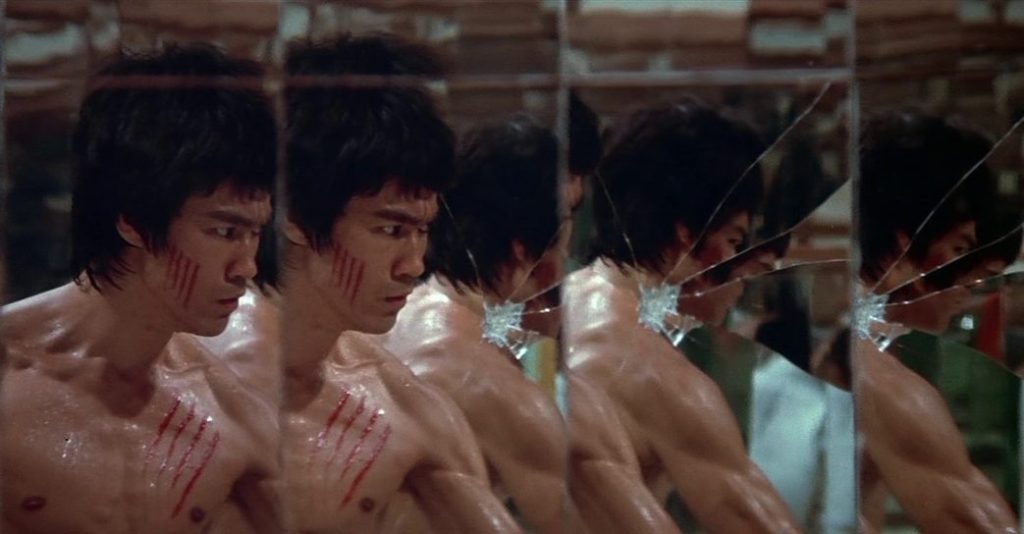

Enter the Dragon’s success also rested on the commodification of countercultural desires emerging in the wake of the Vietnam War—a period marked by skepticism toward the American military state, an interest in New Age remedies, and an affinity for the East’s perceived anti-violence philosophies. Lee embodied these desires through his philosophical teachings of discipline and self-agency, demonstrated on screen through both his ideology and its cinematic enactments. For example, in Enter the Dragon, Lee triumphs not only in physical combat against opponents on Han’s island but also through strategic philosophy, as when he lures an aggressor onto a stranded lifeboat after witnessing their mistreatment of the ship’s crew. This philosophical embodiment is further reflected in his invention of Jeet Kune Do—a martial art emphasizing mastery, rationality, and utilitarian effectiveness by adopting the most scientifically sound techniques from all disciplines.

The utilitarian and egalitarian dimensions of Lee’s philosophy, paired with his embodiment of commodified countercultural ideals, resonated strongly with marginalized audiences—particularly Black viewers—sparking interest in martial arts training and inspiring films that celebrated the cross-cultural transmission of Lee’s martial arts philosophy. In this sense, Enter the Dragon can be considered an example of “intercultural cinema.” Yet, this utopian reading is complicated by the metonymic associations audiences may draw between minority existence, as represented by Lee, and success in historically inhospitable spaces like Hollywood. Such representations construct a fantasy of social mobility within rigid institutional structures, consumable through mass popular culture. Bowman describes this fantasy as a simulacrum—a “fake or entirely constructed representation”—which, while offering the illusion of ideological liberation, simultaneously perpetuates subtle forms of subjugation. Through its modes of production, distribution, reception, and narrative content, Enter the Dragon exemplifies what I would call “diasporic cinema,” reflecting co-constructed cinematic practices that bridge transnational, intercultural, and countercultural dimensions.

Leave a comment