Buddhist culture, as understood through our reading of Pema Tseden’s filmography and mode of production, is inextricably linked to Tibetan culture – an association that becomes especially intriguing when we consider Tseden’s intention to construct a “New Tibetan Cinema”. This emerging oeuvre, which includes Khyentse Norbu’s film The Cup, encourages Tibetan filmmakers to cinematically articulate a “positive Buddhist aesthetic” as endogenous – or even synonymous – with Tibetan culture, particularly in light of Tibet’s annexation by China. This cinematic mission serves as a mode of self-mediation for contemporary Tibetans grappling with displacement and diasporic identity.

What fascinates me most is the oscillation between attachment and detachment that emerges in this mode of Tibetan film production – a tension often palpable in the narrative undercurrents of the films themselves. Tseden asserts that Tibetan culture embodies Buddhist dharmas, which are transmuted cinematically through his construction of a ‘geopsychic terrain’ – a cinematic landscape where Buddhist signifiers resonate with the affective power of his expansive wide shots. Drawing on Dan Smer Yu’s article, we might even propose that the transnational nature of Tseden’s films functions as a new form of nationalism. Lacking the ability to physically demarcate a territorial homeland of Tibetan culture, this cinema instead reclaims a notion of homeland through a metaphysical facsimile: a cinematic world into which its inhabitants – and its audience – can enter.

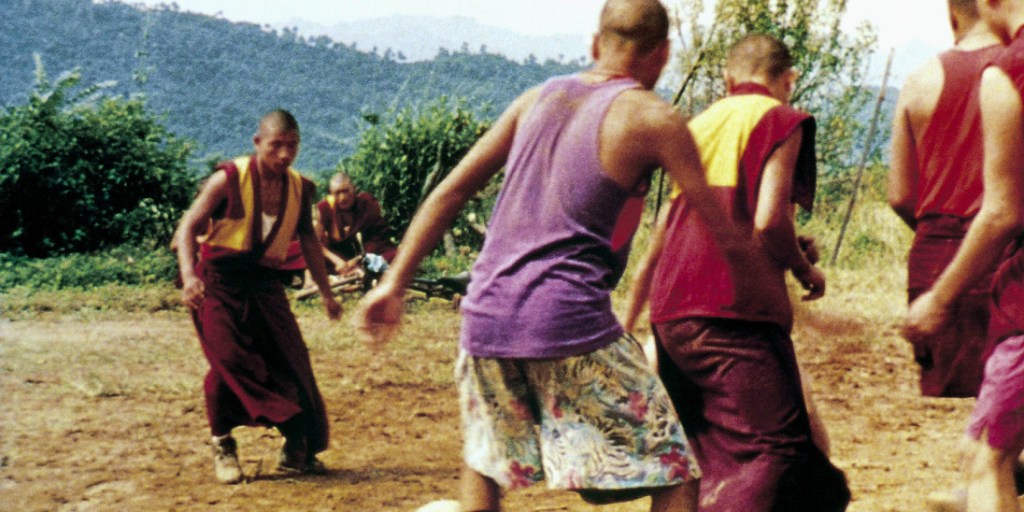

In our particular study of Norbu’s The Cup, Buddhist signifiers are ambivalently interwoven with symbols of encroaching modernism, as experienced by the monastic community. This is evidenced by the repeated presence of the Coke can and the young monks’ constant desire to watch the World Cup. Such modern elements can be seen as “destabilizing to traditional Buddhist practices in Tibet”, yet it is precisely the dialectic between these opposing forces that reveals their mutual imbrication. When framed through the concept of the “tantric gaze” – proposed by Whalen-Bridge as the “yoking of desire” and its aversion as a path toward Buddhist aims and teachings – these secular interests might indeed be understood as a pathway to divine learning. The sage’s reappropriation of the Coke can as an incense holder vividly demonstrates how Buddhist dharmas, so closely identified with Tibetan culture, can emerge from any object – even the most commodified.

So what then can be made of the protagonist’s desire for a Tibetan soccer team to play in the World Cup, and of Tseden’s co-creation of a “New” or “Native Tibetan cinema”? Is this tantric yoking an attachment to the ownership of a homeland that serves as a gateway to the divine dharmas of Buddhist teaching, or is the homeland itself an antecedent to the ability to practice Buddhist dharmas, which remains deeply intertwined with Tibetan culture and identity. Perhaps this tension is central to the work of contemporary Tibetan filmmakers like Norbu, who introduces two young boys into the monastic world of The Cup mainly as a result of a need for safe harbor in lieu of exile. The boys gradually assimilate to monastic life, exchanging their modern clothes for robes and shaving their heads, yet the youngest clings to a material keepsake – a watch given by his mother – as a tangible connection to his family and former life.

This almost imposed adoption of an ascetic lifestyle creates tension around what one might be allowed to miss, particularly when their displacement is not voluntary. This is the core symptom of Tseden’s later films, whose “missing” of his remembered homeland manifests itself in an almost desperate striving to rescue a Buddhism he believes to be fragmented. One he views as scattered and partially memorialized by young contemporary Tibetans who are more easily swayed by modernity’s erosion of tradition, globalization’s effect on the diasporic Tibetan community – a criticism that might otherwise simply be Tseden’s own resistance to the manifestation of a new Tibetan culture, one born of an exiled people existing in the liminal space between borders and identities.

Leave a comment